The Hasidic Rabbi Yehuda Leib Alter of Ger, who died in 1905, wrote:

In the soul of every person there lies a hidden point that is aflame with the love of God, a fire that cannot be put out. Even though ‘it may not be put out’ here refers to a prohibition, it is also a promise. Thus our sages said, ‘Even though fire descends from heaven, it is a commandment to bring it from a common source. (Sefat Emet on Vayikra, Tzav 3:23)

The message of Rabbi Yehuda, known by the title of his work, Sefat Emet, is that we must not put out the fire of tradition, but at the same time, we should understand the promise that the fire will never go out because of our commitment. The challenge of living a Jewish life in modern times is that we all have the choice to opt out, to just say we are not interested in Judaism. We speak about keeping the flame of Judaism alive, but at the same time, that isn’t the best argument for why be Jewish. To say, “I am involved because that is what my parents and grandparents did” is not a strong positive message. Judaism may have mattered to them, but why does it matter to us?

This is what the wicked child asks at the Passover seder, and I have always felt that it’s actually a good question. What does this all mean to you? There has to be a reason we do it. The fire comes from heaven, but we are commanded to bring it from a common, meaning a human, source. We have to find our passion in the tradition, something we love, and we connect to. It can’t just be a prohibition; it must be a promise. We have to find a way for our inner light to connect with the light that was given to us and which we must give to the next generation.

These were the questions that were animating Jewish life in the 1960s and 1970s in America and at Adath Israel, which we celebrated at a centennial instrumental Shabbat service on March 31, 2023. In fact, that is literally the theme of the 40th anniversary journal of 1963, one of the best anniversary books I have ever read: “The Heritage of our Fathers is the Inheritance of our Children”. On Sunday, January 20, 1963 the community held a Fortieth Anniversary Banquet and Annual Meeting of the Congregation featuring a dramatic narrative and documentary entitled “With Grateful Hearts”.

These decades saw major turmoil in the world with social and political revolutions: the fight for civil and women’s rights, the rise of the counterculture, a search for meaning among the Baby Boom generation. People were not willing to just do what was done before, they wanted to make it their own. In the Jewish world, this time period saw the growth of the chavurah movement, which was a rejection of the established Jewish community.

As for Adath, in 1963 Rabbi S. Joshua Kohn wrote:

Today we possess a synagogue with about seven hundred families, a school with more than three hundred fifty children, a youth group with one hundred boys and girls, a Hebrew High School class that attends Gratz College every Sunday, a fine Men’s Club, a very active Sisterhood, study groups, a Boy Scout Troop, a Cub Scout Troop, Art Festivals and many other activities.

In many ways, our community was similar back then:

Adath Israel Congregation has never hesitated in its service to the community and to K’lol Israel. The Jewish Community Center has been permitted the use of our facilities for their summer camp program on rainy days. When the Golden Age Club needed a meeting place, our auditorium was available at no charge.

Adath still serves as a bus stop for the Abrams JCC Camp and still hosts of the Golden Age Club, but somethings were different. Back in 1963 there were a whopping 48 members of the board of trustees. The current number of members is significantly lower. In addition, the 40th anniversary journal reads:

The daily minyan increased and Mr. Ichael Garb felt that a permanent Shamash was needed. Reverend Michael Traugut, a refugee and observant Jew was engaged as the first Shamash. He began his duties in the Fall of 1949 and he now became a very busy person … In the Fall of 1959, an Oneg Shabbat was sponsored by the congregation honoring Mr. Traugut on his tenth anniversary with Adath. His sudden and untimely death in the Spring of 1961 was mourned by all. The second Sexton of Adath Israel is Mr. Morris Silver who joined us in September of 1961.

The role of the shamash was to organize the daily minyan and other services, read Torah, and make sure other rituals matters were properly attended to. While Adath was devoted to tradition, social change did come to the synagogue, if slowly:

The Sisterhood has always been an inspiring force behind the affairs of our Synagogue. Keeping in mind the well-being of the members, Sisterhood women have fought for the reforms to bring the women of the Congregation to their rightful place. This is illustrated by one comment appearing in the minutes that the Sisterhood President announced several coming activities of the Sisterhood. “She also made the usual demands of the men”. We can rest assured that these demands were in the best interests of the majority of the members.

According to the journal,

The first Bat Mitzvah took place on March 3, 1961 when Ruth Alexander ascended our Bimah and chanted the Haftorah. Bat Mitzvah is limited to those girls who continue with a more intensive Hebrew education.

I believe the date of this milestone might be a typo. Ruth Sugerman, née Alexander, is still a member of Adath, but her birthdate does not match a March 1961 bat mitzvah. It would, however, match up well with a March 1951 date.

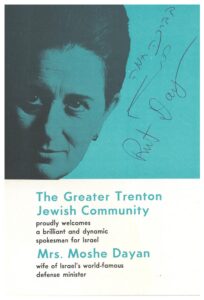

As was shown above, Adath has always been a community-minded synagogue. On December 12, 1971, the synagogue hosted an Israel Bonds dinner dance welcoming Mrs. Moshe Dayan, wife of Israel’s defense minister. The evening included greetings by Adath member Dr. Milton Palat, general chairman of the event. The speaker Ruth Dayan autographed “with warm blessing” a copy of the program, which now resides in our Linder Archives.

Dayan is a great example of the effects of the tremendous social change of the time. While she is called “Mrs. Moshe Dayan” in the program, she was a social activist and entrepreneur in her own right. She divorced her husband in 1972, not long after the event at Adath, and died at 103 in 2021. In the 1950s Dayan founded Maskit, Israel’s only fashion house at the time, which gave jobs to new immigrants who brought beautiful embroidery skills and fabrics to the designs. She was also a dedicated advocate for peace and a lifelong friend of Yasir Arafat’s mother-in-law.

Things were quite different for Adath by 1974 when the congregation conducted an opinion survey of the membership under the leadership of, among others, Elaine Lavine, Joan Eros, and Roz Gross, all still members of the synagogue. All the upheavals changed society and Adath had to deal with these new realities. People didn’t have the same attitudes toward Judaism and tradition as the previous generation. The synagogue had shrunk to 507 members, 35% of whom lived in Trenton, 29% in Ewing, 20% in Yardley and only 6% in Lawrence.

The community was beginning to think about relocating, but 63% were satisfied with the present location of the synagogue and only 22% thought Adath needed a new building. Of the few who wanted to move, the preference for new location was: Yardley 32%, Ewing 20%, Lawrence 22%, To suburb 26%. It’s interesting to think about the alternative universe where Adath moved to Yardley instead of Lawrence.

On the question of ways to enhance services, the membership in 1974 responded in ways that any synagogue leader would recognize. That is, without any real consensus. 24% wanted the sermons to be more political, 26% wanted them to be more Judaic, and 45% wanted them to remain as is. Unsurprisingly, 32% thought the length of services was too long, 68% thought they should remain as is, and exactly 0% thought they were too short. Regarding music, 27% wanted more cantor, 32% wanted more choir, and 30% wanted more congregational singing. When asked about English in the services the responses were that 30% wanted more, 5% desired less English, and 65% were happy for the ratio to remain as is.

Through all these revolutions and change, Adath has always stayed true to the same principle, expressed in 1963: “The Heritage of our [Ancestors] is the Inheritance of our Children”. What have we inherited, what was given to us by our parents and grandparents? How can we add something special, the inner fire that burns within us so that when we pass that heritage on to our children, it’s a bit different, but recognizable to our ancestors? In the soul of every person and in the soul of every community, there lies a hidden point that is aflame with the love of God, a fire that cannot be put out. It’s not just a prohibition or a description about Adath’s past; it is also a promise for our future.